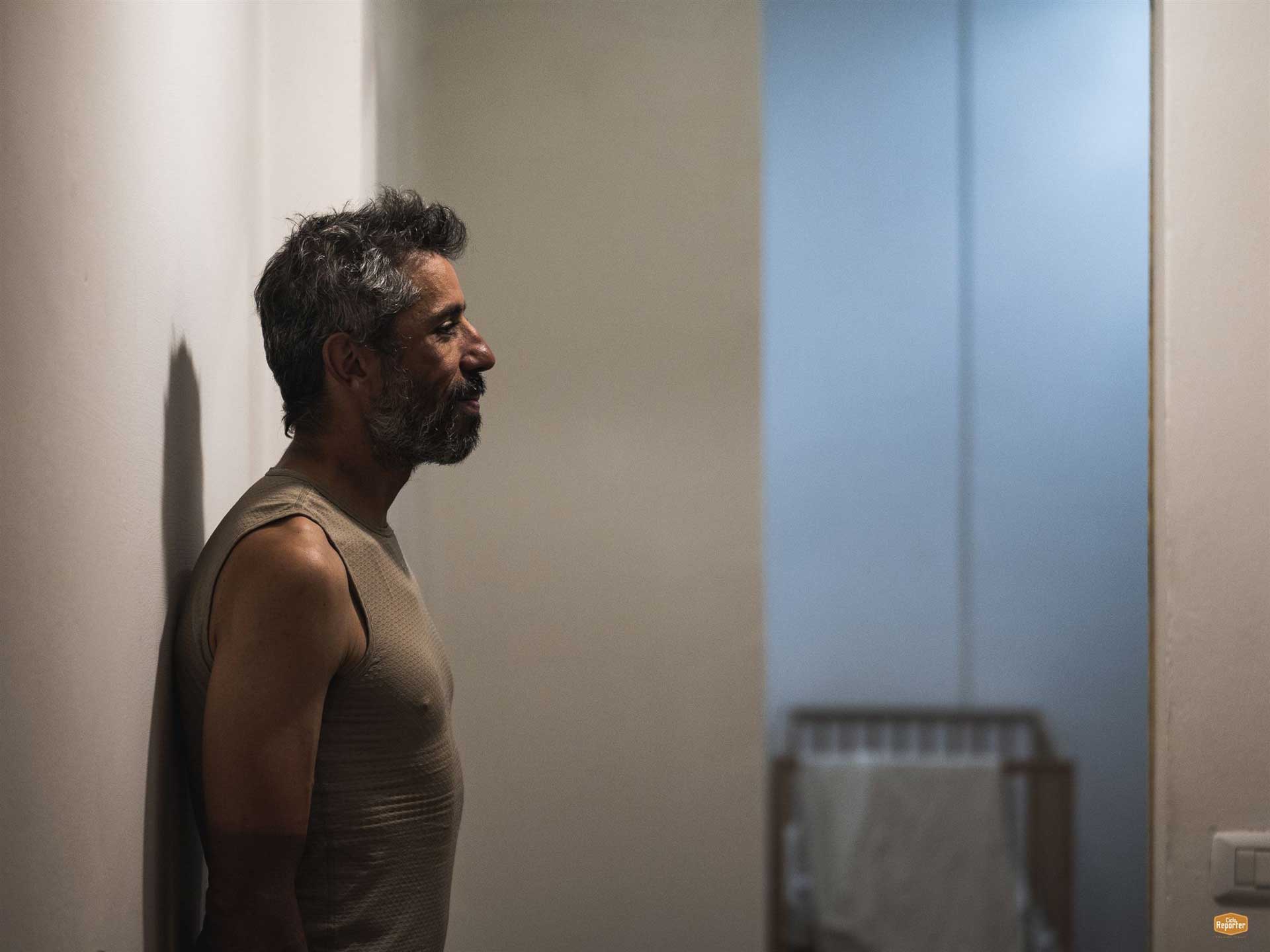

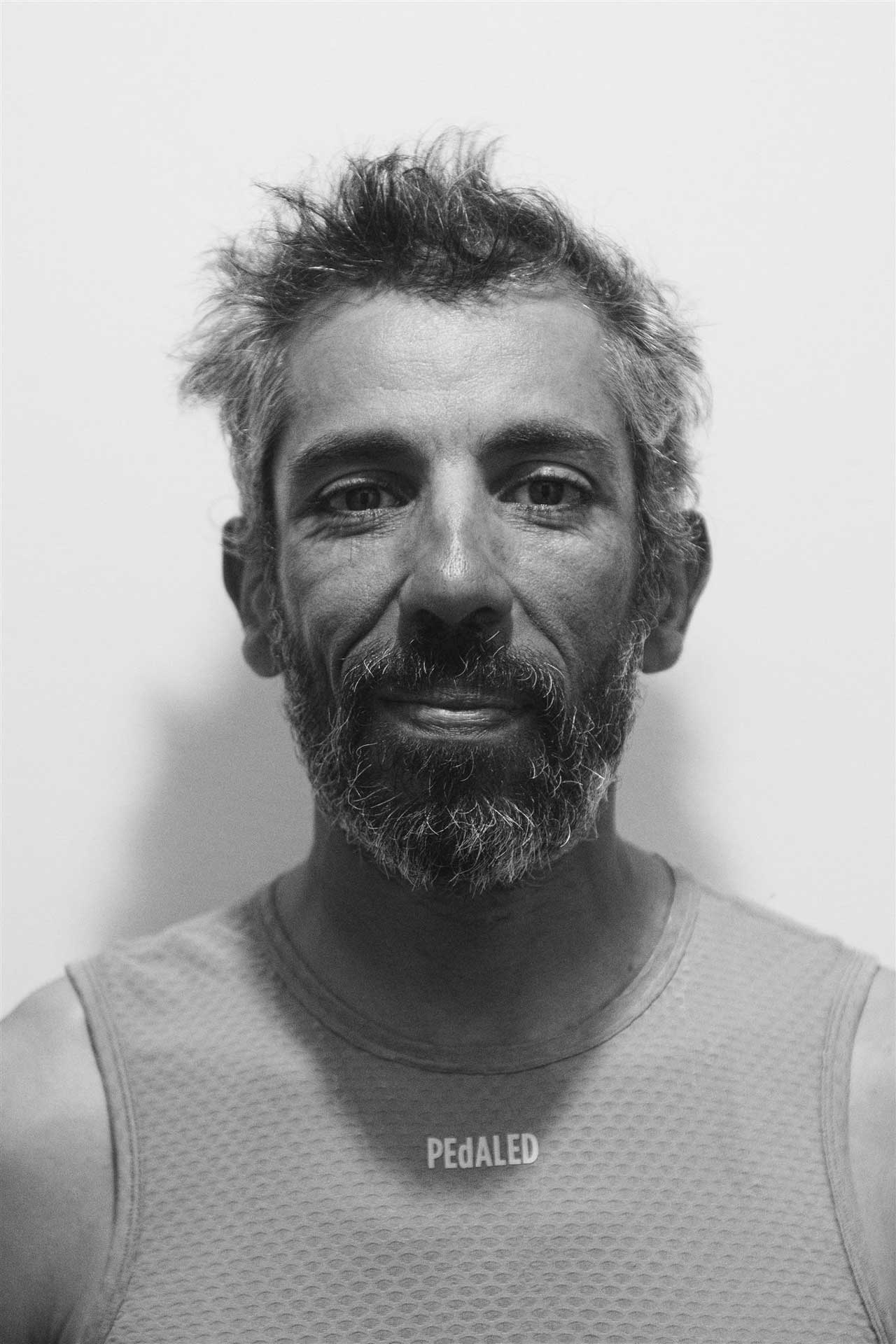

This summer, our ambassador Sofiane Sehili attempted to become the fastest person to cycle across Eurasia, starting in Cabo da Roca, Portugal, and finishing in Vladivostok, Russia. His journey kept us on the edge of our seats as he pursued this extraordinary record—a challenge that involved covering nearly 18,000 kilometers in just two months. While media attention largely focused on the dramatic end of his adventure and his detention in Russia, we want to highlight the extraordinary sporting achievement that preceded these events in this exclusive interview. Sofiane’s performance was an incredible feat of endurance, determination, and courage—an achievement that deserves to be recognized and celebrated. For our part, we are very proud to have contributed, however modestly, to this sporting achievement, as Sofiane was using the KS Ether gravel cockpit. Of course, you have certainly followed the outcome of Sofiane’s adventure; Thankfully, everything turned out well and we were all immensely relieved to see him regain his freedom.

It’s hard to imagine that there’s any training specifically “adapted” to such a crossing. How did you prepare physically for this challenge? I ride 100% of the year. When you’re a pro ultra runner, there’s no off-season. Especially this year, with a very important event right from February (the Atlas Mountain Race). The real challenge is recovering properly between races. They’re obviously very demanding, and you don’t finish them in top form. In May, I participated in the Trans Balkan Race, so the whole point for me was to make a smooth transition between that race and the record attempt. Recover well, then get back into it at the right time.

Did you have a specific training program, or did you think, “I’ll start in good shape, and my body will adapt on the road”? I didn’t follow a specific training plan. I think they’ve become essential in many cycling disciplines, but not necessarily in ultra-distance running. I’ve been doing long-distance running for about ten years, so I have my bearings. I know that over two months, you can start a little below your usual level, and that at some point, the rhythm will come. The important thing is to know your body perfectly and how it reacts to repeated efforts. I knew, for example, that the heat was going to be one of the biggest challenges of this attempt. I didn’t have time to prepare for it beforehand, so I just went for it, thinking: I’ll adapt along the way. As a result, I suffered a lot at the beginning, but after a good week, my body reacted better to the efforts made in very hot weather.

Beyond the physical aspect, how do you mentally prepare yourself to spend two months alone on your bike, stringing together entire days of effort, often in extreme conditions? It’s the experience of several years spent not only on the ultra-cycling circuit, but also on my own long-distance journeys. Before deciding to embark on an adventure like this, you need a certain love of solitude. If you can’t stand being alone with your thoughts, then it’s better to do something else. Being alone in deserted spaces, in absolute calm, is the very reason I cycle. Of course, after five or six weeks on the road, you start to want to go home, to see your loved ones, to be back home. But when that moment arrives, you’ve gotten so close to your goal that nothing can deter you.

Anticipating… without controlling everything. When preparing for an impossible journey like this, how far can you go in planning? It’s incredibly difficult to anticipate everything. And I don’t even know if it’s desirable. Adventure is precisely about the unexpected, letting yourself be carried away by the unforeseen. The important thing is to be ready for any eventuality. On a physical and mechanical level, you shouldn’t leave anything to chance. For the rest, you can be flexible. But as long as you’re moving forward, that’s the main thing. The essential thing is to always be in motion, in the right direction. After that, which country, which road, what surface, at what speed—that’s secondary.

Did you plan everything—route, stages, resupply points—or was there a lot of room for improvisation, depending on the weather, fatigue, and encounters? When I travel, I like to set off with a general idea of where I want to go, but nothing too specific. I’m convinced you have to be flexible. Otherwise, you get bored. In any case, planning everything for 18,000 km is impossible. One small hitch can ruin the whole plan. And, in my case, the surprises started on day one. I suffered terribly from the heat in Portugal, and my first stage was much shorter than I had imagined. After that, I had to adapt. In the end, quite a few things changed compared to the route I had initially planned. For example, when I arrived in Kazakhstan, I found the roads too dangerous and changed my plans: instead of the Kazakh steppes, I crossed the Uzbek desert and the Tajik mountains. It cost me time, but it gave me peace of mind and offered me some of the most beautiful rides of this trip.

On such a long journey, unexpected events are bound to happen: a breakdown, a complicated border crossing, an off day… How do you handle these kinds of situations when there’s no support, no support vehicle? It’s once again a question of experience. I started traveling by bike about fifteen years ago. I’ve had time to learn how to manage most mechanical issues and resolve all sorts of problems. I think that in terms of bikepacking, there are very few truly unsolvable problems. For example, in Tajikistan, I twice found myself without money and with no way to withdraw any. The first time, by asking passersby in the street, I managed to find some black market money changers who agreed to buy a $100 bill from me. The second time, I went around to all the guesthouses and finally met a Dutch tourist on his way to Kyrgyzstan who gave me Tajik currency in exchange for a bank transfer. What I find interesting about a record attempt like this is that to succeed, you can’t just pedal mindlessly. You have to be resourceful, inventive, and have the soul of an adventurer.

So, without a support team, how do you find the right balance between the essential equipment to prevent technical problems and the need to travel light so as not to hinder yourself physically? There are things you can buy almost anywhere in the world, like inner tubes or patches. The rest you have to carry with you: brake pads, spare spokes, derailleur hanger, chain links. Over the years, I’ve made a list of things that weigh nothing, take up no space, and could save my life. I always carry them with me. I had also planned a package, sent to Kazakhstan from home, with tires, a cassette, and a chain. The bad news is that it never arrived. The good news is that my cassette and chain lasted 18,000 km. As for the tires, that was quite a challenge, but I finally managed to find some in a shop in Ulaanbaatar.

Spending two months almost entirely alone on the roads of the world is a rare experience. How do you experience this solitude on a daily basis?

Is it something you endure, or on the contrary, a space of freedom you seek? It’s not something I fear or endure at all, quite the opposite. My most beautiful journeys have been in the Pamir Mountains or on the Mongolian steppes. Places where the roads are deserted. Where you only find a village every hundred kilometers. I grew up in the Parisian suburbs and have lived almost my entire life in or near Paris. When I started traveling by bike and discovered what it was like to find myself in the calm of absolute solitude, it was a revelation for me. It’s no coincidence that I specialized in gravel and mountain biking. It’s by taking these unpaved roads and these lost trails that I can reach these places where the intoxication of solitude is purest.

And then, when you’re focused on performance, pedaling hundreds of kilometers every day, do you still manage to appreciate the landscapes, the cultures you encounter, those moments of grace? Yes, thankfully. Of course, it’s not the ideal conditions for enjoying it. Because often, you’re fed up, tired, or simply in a hurry. But when you’re in the saddle for 12 to 16 hours a day, you still have many moments when you manage to be in the right frame of mind to truly savor the joy of being outdoors, the curiosity of discovering cultures so different from your own, the happiness of witnessing the beauty of nature. That’s the magic of cycling. As for the magic inherent in long-distance cycling, it’s sometimes those moments of grace that occur at the end of a grueling or rather uninteresting day, and which somehow redeem it and give it all its meaning and purpose. For example, the soft, orange light of twilight reflecting on a canal transforms the landscape, just as you leave a busy road for a small country lane… and in a few minutes you can forget 12 hours spent being bored.

Was there a moment, an encounter, a place, where you thought to yourself, “This is why I’m doing this”? There were several. I remember a 380km leg in Mongolia, propelled by a westerly wind through magnificent landscapes and an unreal tranquility. That feeling of flying, almost effortlessly, and the asphalt unfurling like a red carpet. Discovering the mountains in western Turkey. Or the welcome I received from a hotel owner in China at the end of a rainy day. She took care of me as if I were family. She brought me dry clothes and served me a good hot meal when I got out of the shower. She was the encounter that transformed what had been such a trying day into one of the most beautiful memories of this trip.

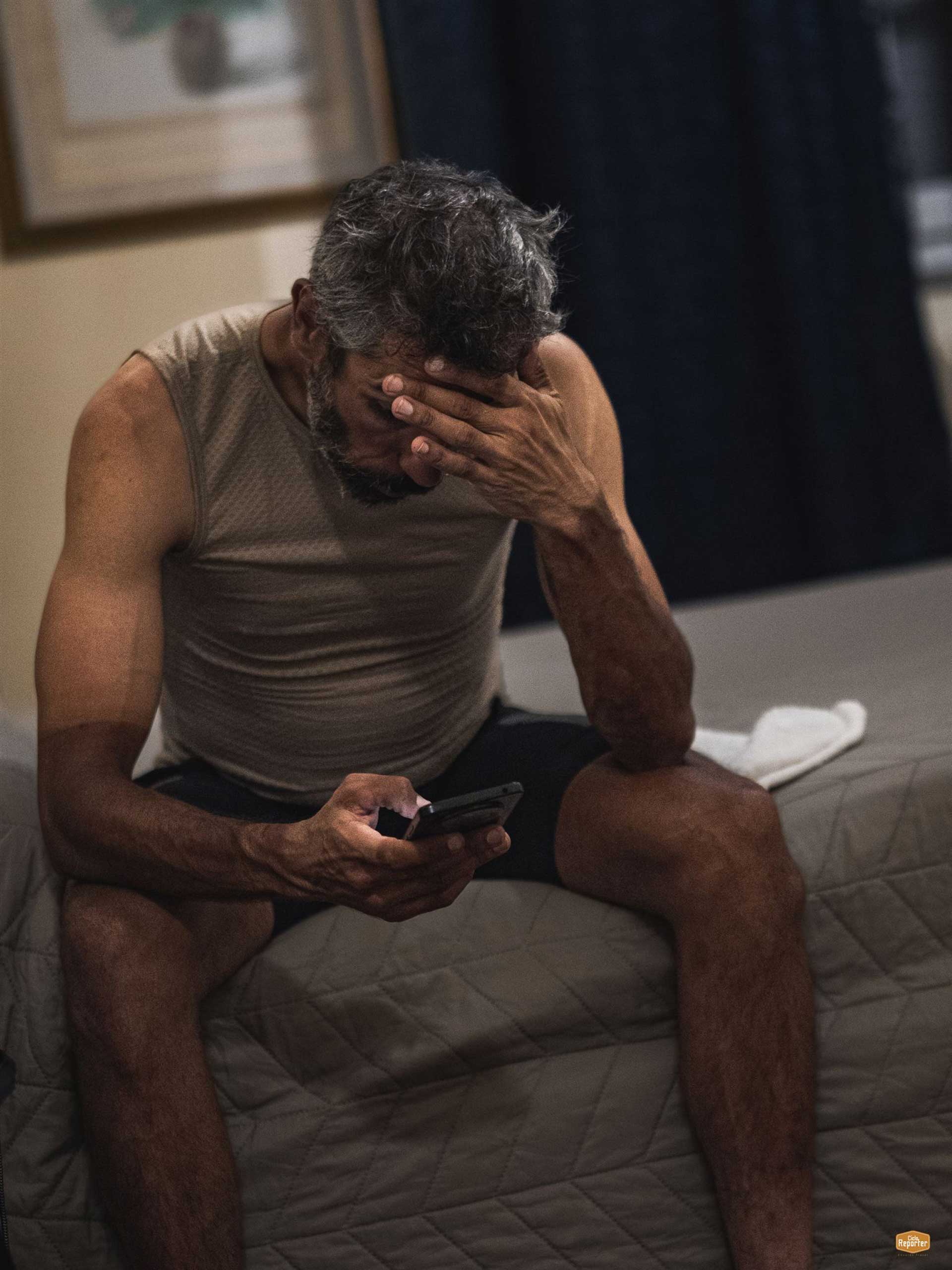

Beyond the sporting challenge. After such a journey, and especially its epilogue, we imagine you didn’t come back quite the same. What did this experience teach you about yourself, your limits, or how you see the world? It was two intense months. Two months where cycling was my whole life. Where I transformed into a kind of machine obsessed with progress at all costs. And where my usual life, the one outside of cycling, became more and more unreal as the days went by. On the one hand, it was exhilarating. But on the other, it gave me this strange feeling of becoming too detached from my normal life, and especially from my partner, who is also a cyclist. I realized that at this stage of my life, while there’s still room for solo adventures, I no longer really want to live such intense experiences alone. I prefer to share them, perhaps by taking more time for exploration. Now that I’ve built a lasting relationship, I don’t want my partner to be excluded from such significant experiences. Going away for a month, seeing one or two countries, okay. But two months, 17 countries, I won’t do that anymore.

And now that it’s done… how do you handle the “aftermath”? Is there a feeling of emptiness, or are you already thinking about the next project? It’s hard not to think about the road, the exhilaration of travel, of discovery. About this nomadic life, stripped of superficiality, where everything has meaning, where everything is simple. It’s in my blood, and I never feel as happy and alive as when I’m on my bike, elsewhere, in those distant lands where almost everything is foreign to me. I’m absolutely convinced that I was made for this, that I’m lucky to have found exactly my path. But there’s a time for everything. And to fully appreciate travel, you also have to know how to slow down and rest. I miss bikepacking a little, but I’m still happy to be home. The next trip will take place at the end of the year and will be much less extreme: 1500km in Morocco with my partner. But after 18,000km alone, I can’t wait to share the road with her, at a different pace, without the pressure of a record.

Photos: Edgar Santos, Josh Ibbett, Edoardo Frezet, Matteo Secci

Read more about Sofiane: Sofiane Sehili: The ultimate authority in ultra endurance cycling

Watch Sofiane’s video on YouTube: Ultragravel cycling masterclass by Sofiane Sehili

Learn more about the KS products choosen by Sofiane for his adventure: